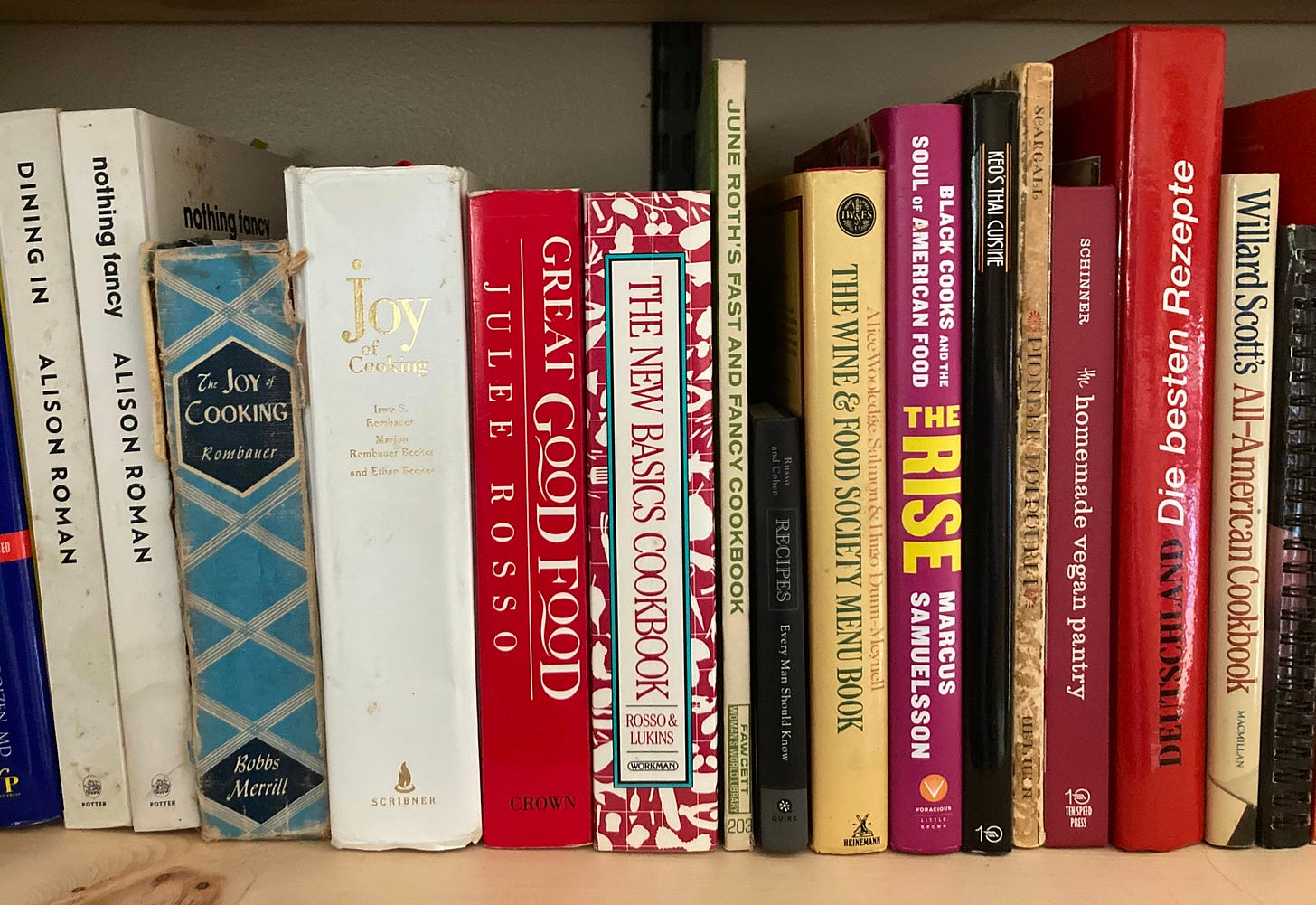

When I look at my cookbook collection, I see a lot of incredibly good cookbooks I use confidently, knowing they have been well tested and designed. Bethlehem, Indian-ish, and Black Food are gorgeous books that tell compelling stories. Small Victories and Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat truly taught me to cook after growing up in a Midwestern casserole household. Books like Pasta and Mastering the Art of French Cooking are meticulously detailed, helping you conquer complex dishes with the necessary handholding.

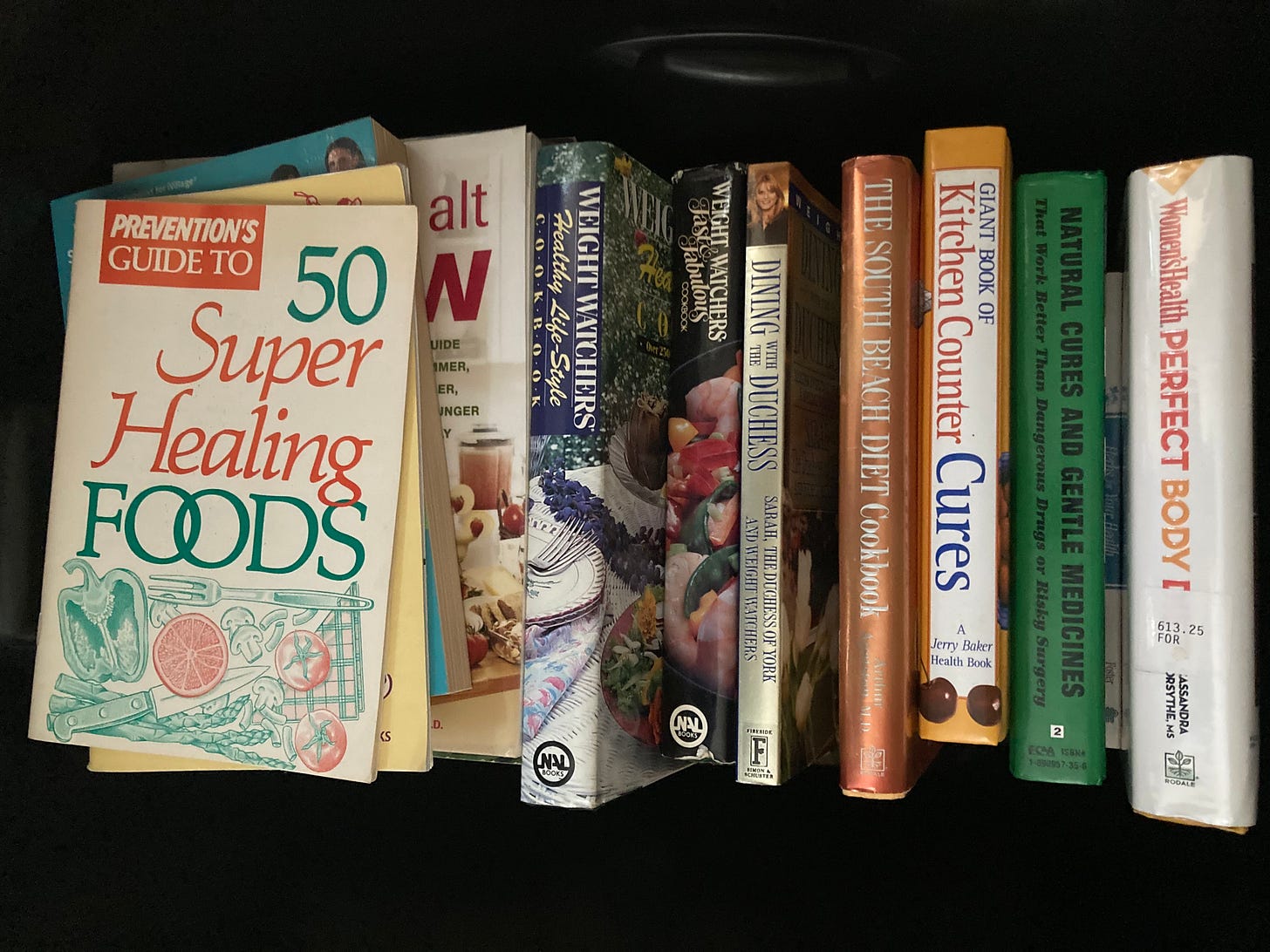

I also have an entire plastic tote of diet books from the 1980-90s, an entire shelf of vintage Betty Crocker (including the Microwave Cookbook), and four boxes of brand booklets covering everything from baking soda to Crisco to electrifying your kitchen. My books range in age from 1890-2024, from 3”x5” to coffee table size, a few pages to hundreds. Illustrations, photographs, and dramatic typography of various quality grace the pages. The seeming lack of cohesion and quality control might be dizzying to some.

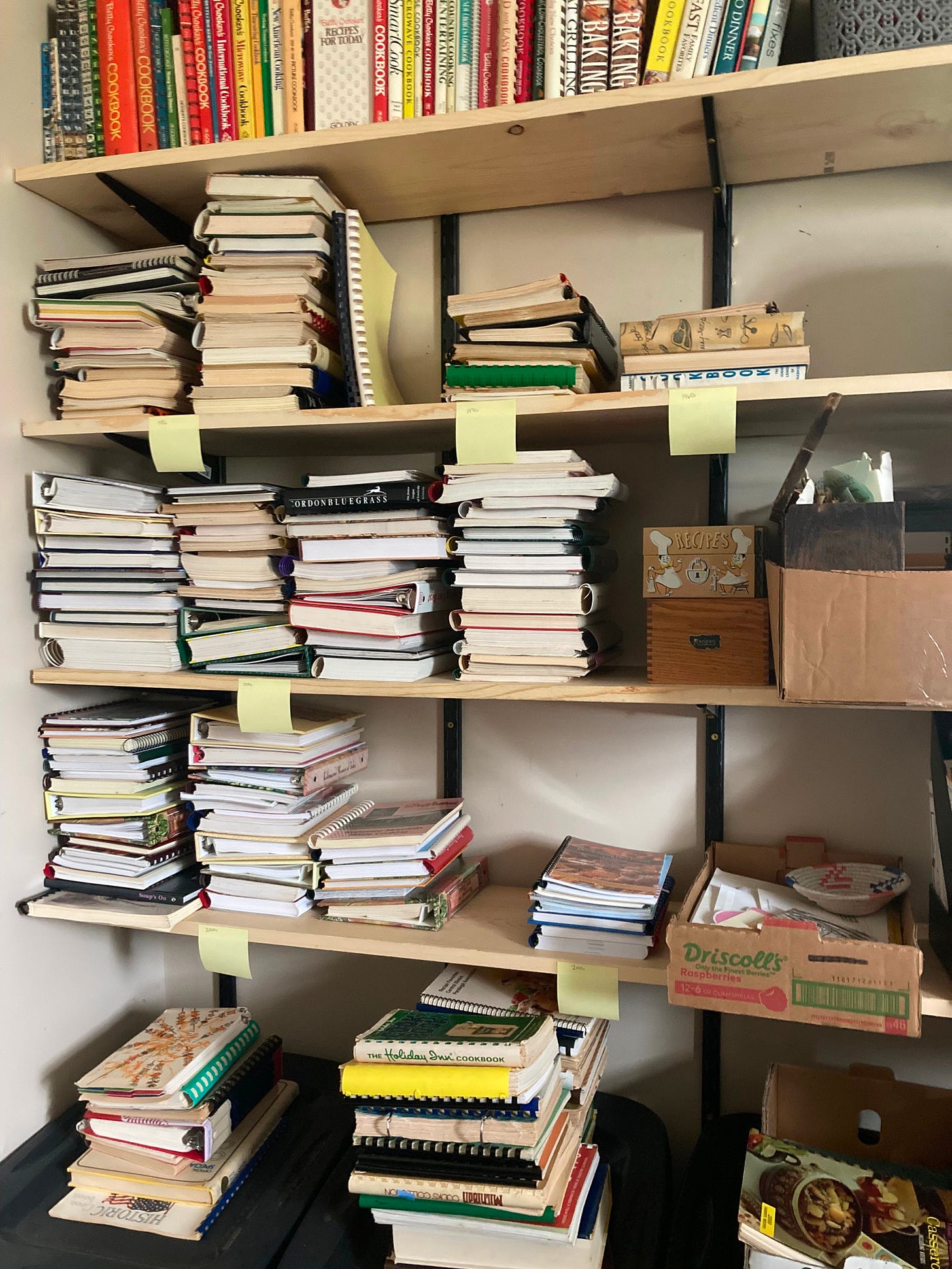

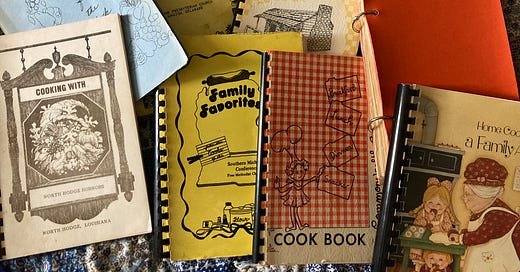

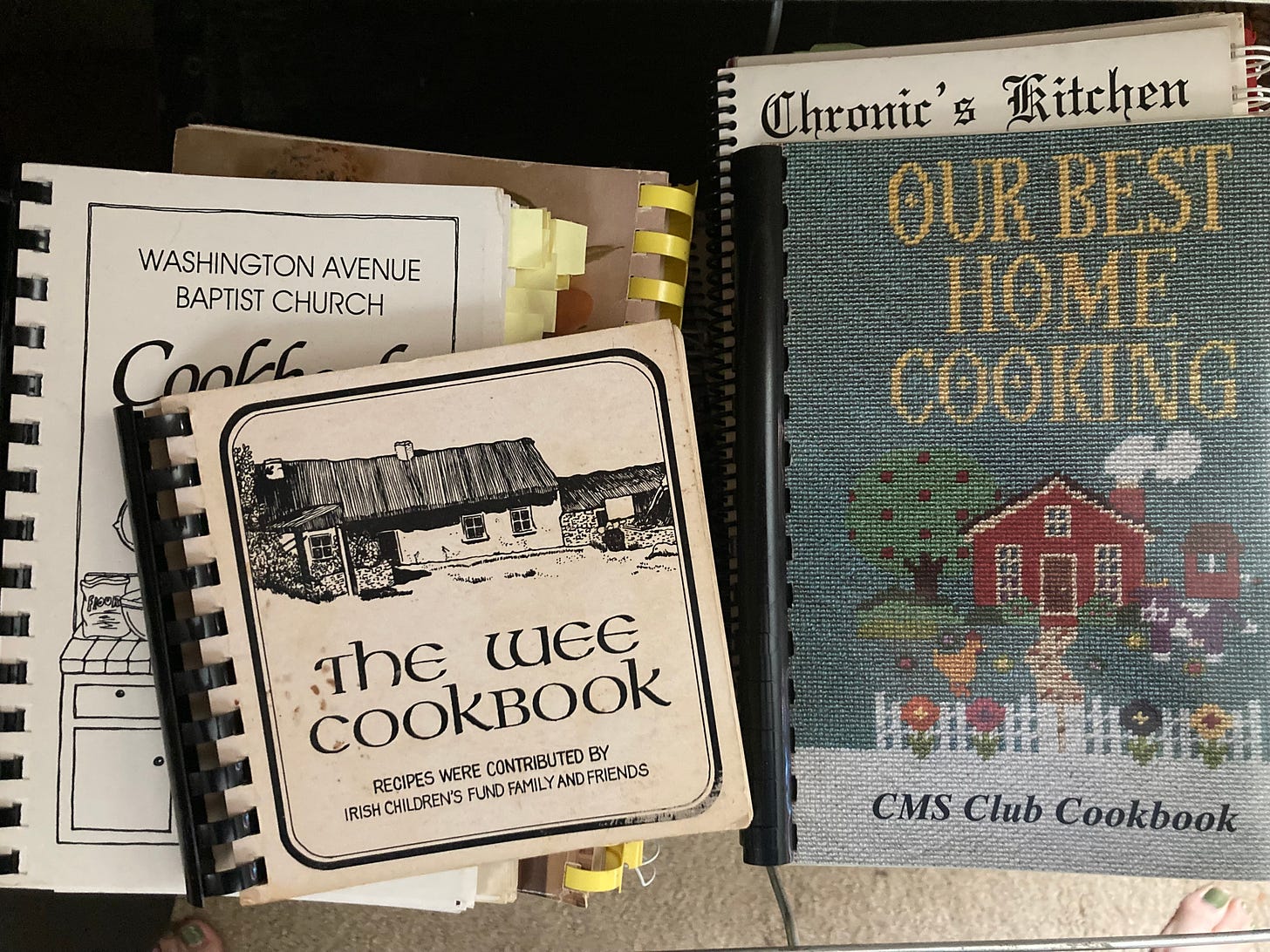

There is a section of my collection, however, that ties all these books together: directly to the left of my desk are four shelves of community cookbooks and handwritten recipes. Community cookbook and handwritten recipes are often poached from the pages of brand booklets, all-in-one style cookbooks, diet cookbooks, and celebrity cookbooks with slight modifications, making tracking down the origin of these recipes difficult if you don’t have access to popular-then-but-terrible-now books from the time period. My collection is varied, almost to a fault, in an attempt to try and piece together the story of what people ate.

What Makes a Cookbook Bad?

Recently on Substack there have been a couple of great articles about what to look for (or avoid) when buying a cookbook. I have agreed with so many of the points made, but something was bothering me at the back of my mind. I just couldn’t put my finger on it, and I came to realize it was shame. I own a lot of bad cookbooks.

Based on all the standards I’ve recently seen about what makes a cookbook “good”, community cookbooks are terrible. Ingredients lists with missing items, vague directions, forgotten oven times, falling-apart-bindings, illegible type; you name a problem and I’m sure I have an example. They are difficult and frustrating to cook from. These are the messy and imperfect recipes of home cooks, in their own words.

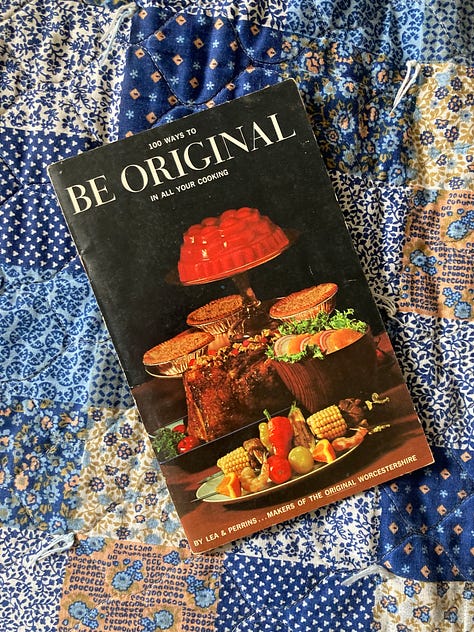

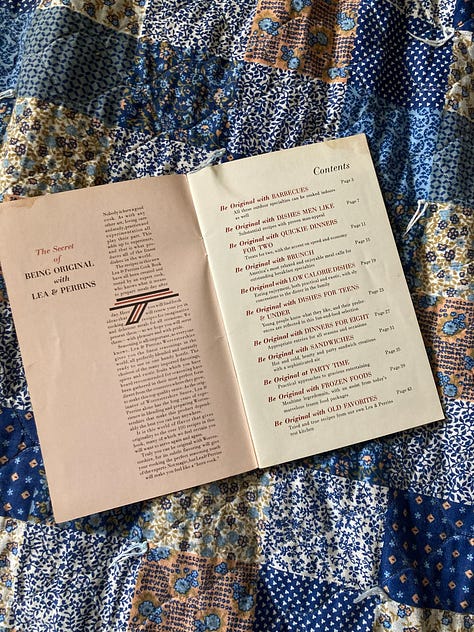

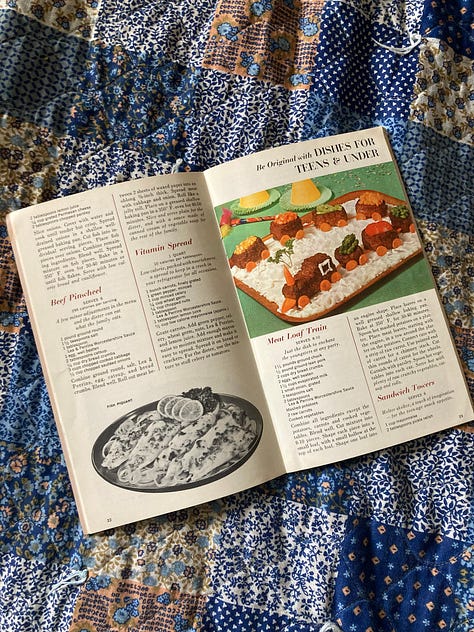

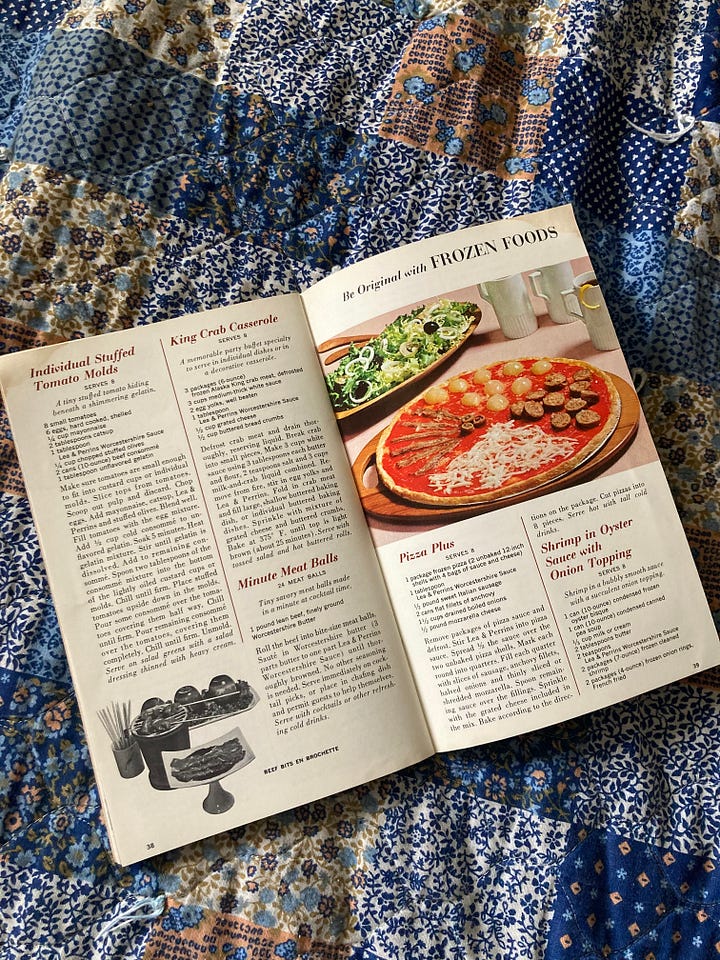

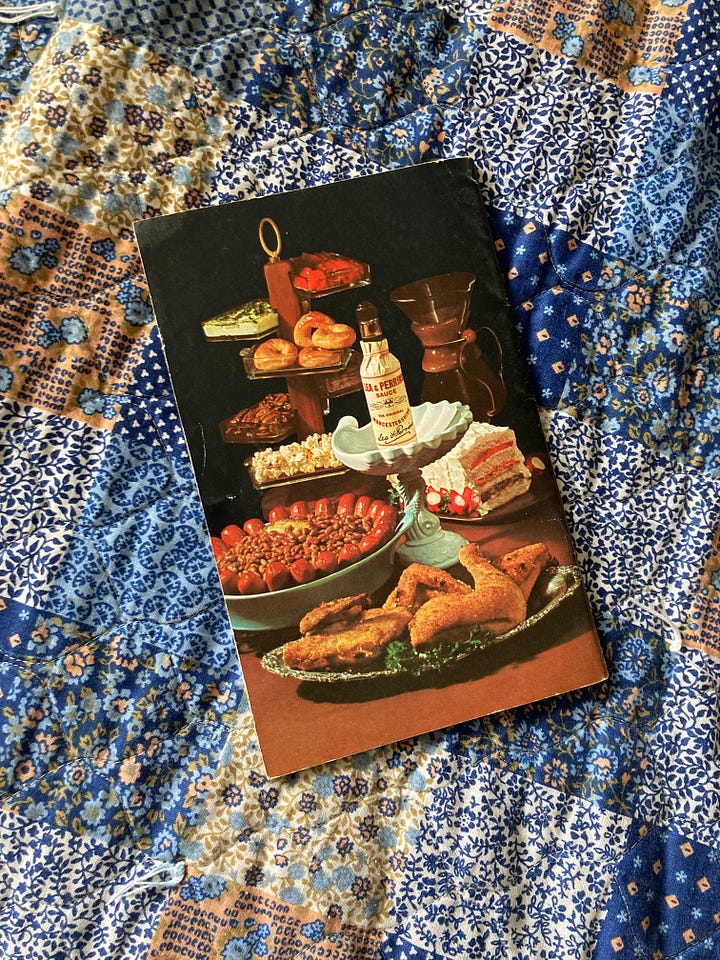

Brand books and booklets also have a tendency to be awful. The pressures put on home economics departments of yesteryear meant that companies produced recipes containing branded ingredients that had absolutely no right appearing together. My favorite example of this is a Lea & Perrin’s brand book from the 1960s(?). The recipes are not good. At all. But at the time, this was a way for companies to advertise their products marketability, and this was Lea & Perrin’s attempt to move their product beyond Bloody Marys. I’m sure many of these recipes were never cooked outside the Lea & Perrin’s Home Economics Department, but some of them did seep into the public lexicon, for better or worse. These advertising pushes worked and impacted how food was prepared.

Overall? Most of my collection contains objectively “bad” cookbooks.

“Hi, My Name is Hannah, and I Collect Bad Cookbooks”

Ok, that might be a little tongue-in-cheek, I admit.

But at the end of the day, as much as I adore a brand new cookbook with immaculate photography, perfect measurements, and thoughtful prose, I equally adore finding a staple-bound pamphlet put out by my local gas company 60 years ago trying to persuade housewives that their cookies will taste better in a gas oven. Nothing, absolutely nothing, tops the high of finding a stained, back-cover-missing, spiral bound church cookbook that contains 45 gelatin salads, a yeast bread recipe you’ve never seen anything like before, and a bunch of handwritten notes. Going through a box at an antique store and realizing you’ve found the exact same Pillsbury Cookbook from 1980 that your mother used as her culinary bible is an unrivaled emotional experience.

Oftentimes when people who aren’t apart of the food world hear I collect cookbooks, or see a picture of my shelves, they ask in a credulous tone “do you cook from all those books?” And the resounding answer is absolutely not.

I don’t buy and collect these books with the expectation they’ll be reliable. Many of them, I have no desire to cook from at all (looking at you, Butter Busters). For me, these books are essential to telling one of society’s most fundamental stories: how we feed ourselves.

Then What Makes a Cookbook Good?

The common underlying assumption, even amongst people outside the food ecosystem, is that if you a buy a cookbook you should be able to open it up and repeat the recipe there with ease. The words and images on the page should inspire you to create, and the results should be repeatable. That is a great definition, and one I think that new cookbooks published by professionals today should be aspiring to as the bare minimum standard.

But at the end of the day, what makes a cookbook good depends on what you’re using it for. There are cookbooks I buy with the intent of cooking from them. I’m a huge fan of Julia Turshen, Priya Krishna, and Michelle Lopez, for example. When you open their books, it’s easy to follow their directions and get the perfect end result. I will probably buy every book they ever write. They are, without a doubt, good cookbooks by incredible authors.

I will also buy every single community cookbook that crosses my path, no matter the age or region. I snag every cookbook about regional cooking (that is actually written by someone from the region), books about cooking with wild plants, and brand booklets with little regard for age or design quality. I don’t buy these books with the anticipation I can cook from them easily, I collect them to read and learn. Because these books are the primary sources of a food culture that, while technically still in living memory, doesn’t actually exist anymore. These cookbooks are good, not as tools or instructional guides, but as cultural artifacts.

In Conclusion…

…whether a cookbook is “good” or “bad” has just as much to do with the book itself as it does with why you’re buying it. Cookbooks occupy an unusual liminal space, where they are both tools and primary sources, making the judgement criteria a bit all over the place.

If you’re approaching them as a home cook just trying to get dinner on the table versus a professional chef aiming to learn an insightful, new technique, your standards are going to be wildly different. If you are, like me, voraciously reading every recipe you can get your hands on because you are endlessly fascinated by the ways we have fed ourselves as a society for the past century and a half or so, your standards are also going to be different. If you’re trying to make cookies just like your grandma used to make, you’re going to think the Betty Crocker Cooky Book is better than Tartine.

New cookbooks, published by professionals, should absolutely be held to the highest possible standards. But I hope we never lose sight of the importance and relevance of “bad” cookbooks as the backbone of the culinary legacy we’re building upon today.

Thank You!

Thank you so much for reading and supporting The Recipe Graveyard! I’m committed to providing this work to all of you lovely readers for free, but here are some ways you can support my work if you appreciate what I’m doing around here and want to help:

Donate through Ko-Fi! You can make a one-time or recurring monthly donation through Ko-Fi to help keep the lights on for this little blog and newsletter.

Buy a cookbook! I often batch buy vintage cookbooks at estate sales, garage sales, and flea markets to cost-effectively grow my collection, so I sometimes end up with duplicates. These will be listed over on eBay!

Visit the site! My blog will soon be running ads, and the payout from those ads is based on views. If you have a spare minute, I’d love if you could go poke around the site. Perhaps catch up on back posts of the blog or look through the resources available in the Free, Open Access Cookbook Index!

Like, comment, or restack this note! As much as we all rue the algorithm, it is the bedrock of getting this work in front of new faces. If you would be so kind as to like, comment, or restack, it will help push my work to a broader audience completely for free!

Follow along on Instagram, Threads, or Pinterest! If you are on social media come find me and say hi! Substack is a lovely place, but it is one of the smaller fish in the social media sea. Interacting on other platforms helps broaden the reach of this little project. And bonus, you’ll get to see fun photos and recipes that don’t always get posted to Notes!

Regardless of whether you’re able to help support this little project or not, I’m so grateful you’re here and reading along! I hope you’ve learned something fun or remembered a long-lost, nostalgic food memory. If you’ve made it this far without subscribing, I hope you consider doing so!

Oh my goodness, I think I could be in heaven in your cookbook library. What a treasure trove! I can look through books like this for ages.

I agree with you about forgotten cuisines being preserved in community cookbooks. Native American cuisine is one example. Online searches suggest things like "Navajo fry bread" but that was actually food they were forced to make once they had been relegated to the reservations and had to somehow make do with government supplied provisions. It's hard to find information about the recipes each of the tribes actually made, much less instructions for how to recreate those foods.

Wow that’s an impressive collection! I love this idea of a cookbook as a cultural artefact. I have a few of my Nans old cookbooks and while many of the recipes look pretty awful to me today, I love them. They say something about when they were written, the ingredients available, the popular styles, and I love seeing the pages she turned down or used the most!